Causes of diabetes related to colonialism and decisions affecting First Nations health and welfare

Colonialism Causes Diabetes, and Other Things I Learned at the Indigenous Health Conference

Andreas Krebs, Political communications professional - Posted: 11/26/2014

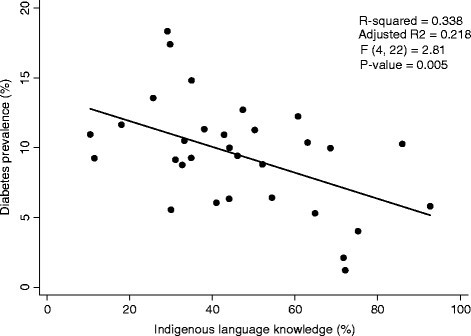

According to new research presented at the first Indigenous Health Conference last week, colonialism causes diabetes. I know, I know, I'm not supposed to talk about causality when it comes to scientific research. But it's pretty hard not to think that way when confronted with Dr. Rick Oster & company's research. Dr. Oster has shown that First Nations communities with a higher proportion of members speaking their native language have lower rates of diabetes.

We know that a key plank of the residential school system was to destroy Aboriginal languages. This was a key plank in Canada's colonial system. So those communities that, for whatever reason, were able to retain their languages have been somewhat inoculated against diabetes.

Indigenous people across Turtle Island are working diligently to recover from colonialism. We can see this in initiatives to recover languages and go back to traditional foods -- both of which show promise in fighting diabetes and other diseases. But one thing that conference presenters made clear is that colonialism is not something that happened in the past. Colonialism is alive and well throughout Canadian society, and the health care system is no exception. In fact, the health care system broadly speaking is a principal way that Canada continues to colonize Indigenous people.

As Natan Obed, Director of Social and Cultural Development at Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated, discussed, one of the ways the health care system reproduces colonialism is through health research. Too often medical researchers treat Indigenous people as objects to be studied, rather than partners in their research. This attitude harkens back to the food experiments done on children incarcerated in residential schools. And while university ethics submissions now include a line for Aboriginal partners, too often health researchers treat such partnerships as a hoop to jump through rather than an integral part of the research process.

The legacy of residential schools also speaks to the importance of incorporating traditional healing into Indigenous health care practices. Keynote speaker Justice Murray Sinclair, head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, noted that for many Aboriginal people in this country, when they step inside a hospital or a doctor's office, they feel echoes of their time in residential school. After all, the institutions have very similar authority structures. This leads many residential school survivors to deeply distrust the medical establishment.

Even when someone suffering from mental or physical difficulties does decide to enter into the Western medical system, they often visit a traditional healer or elder as well. However, this leaves both the physician and the traditional healer in the dark as to what the other is doing, and may complicate care for the patient. A number of speakers at the conference pointed to this lack of dialogue as posing a problem for the health of Indigenous people.

The work, therefore, is in decolonizing the health care system. For most Indigenous people, this means self-determination -- the freedom to choose how to implement health care systems, governance, and what treatments an individual patient may choose. Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and Health Canada both take great pains to cast their programming as enabling First Nations to come to self-determination over their health services. But as Dr. Angela Mashford-Pringle made clear, there is a substantial and qualitative difference between the self-administration being peddled by the federal government, and the self-determination that Indigenous peoples are calling for.

AANDC and Health Canada simply expect First Nations to reproduce the health system found in mainstream Canada, but with Indigenous people administering it. So long as AANDC and Health Canada control the purse strings, there is no room for First Nations to take control of their health in any meaningful way. Doctors and traditional healers will remain at odds; communities will be expected to suffer through the imposition of a cookie cutter approach to their well being; and chronic diseases associated with colonialism -- from diabetes to depression to substance abuse -- will continue to plague Indigenous people.

These problems are massive, and can be daunting. As Justice Sinclair said in his opening remarks, Canadian colonialism won't be resolved within our lifetime. But there are many glimmers of hope out there. Incorporating traditional healing into treatment for substance abuse is having positive impact for patients, and moving addiction treatment towards a holistic approach. Indigenous people are reclaiming traditional foods as a way to reconnect with their cultures -- and prevent diabetes. And British Columbia is the first province to create a First Nations Health Authority, which aims to improve First Nations health outcomes with a culturally relevant approach.

And now health care practitioners have tools at their disposal to better serve their Indigenous clients. Indigenous Cultural Competency Training is an online, live facilitated course designed to enhance self-awareness among health care workers, and build towards a culturally safe health care system. As Vanessa Ambtman-Smith and Guy Hagar showed, their program is working to break down the preconceptions and prejudices -- the racism -- that many Indigenous people face in health care settings. This training won't eliminate colonialism from healthcare on its own -- but it's an encouraging start, and enables non-Aboriginal people to learn more about how to change their own practices to stop colonialism from continuing.

ALSO ON HUFFPOST:

What Affects Diabetes Risk? ShutterStock

ShutterStock