First Nation Education Act another "assimilationist" effort by the federal government warns AFN leader

Stephen Harper's First Nation Education Act might continue assimilation, Shawn Atleo says

BY MARK KENNEDY, OCTOBER 7, 2013

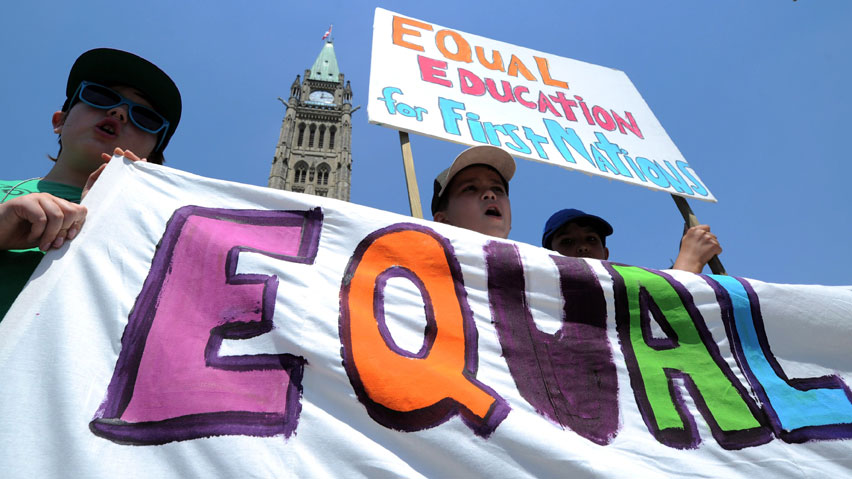

First Nations people are joined by supporters during the Walk for Reconciliation in Vancouver, B.C., on Sunday September 22, 2013. The walk wrapped up a week Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada events in the city. From the 19th century until the 1970s, more than 150,000 aboriginal children were required to attend state-funded Christian schools in an attempt to assimilate them into Canadian society. They were prohibited from speaking their languages or participating in cultural practices. The commission was created as part of a $5 billion class action settlement in 2006 - the largest in Canadian history - between the government, churches and 90,000 surviving students. Photograph by: THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck , Postmedia News

OTTAWA - The Harper government is on the verge of potentially imposing an "assimilationist" education system on aboriginal children that repeats the mistakes of residential schools from past decades, says the head of Canada's largest aboriginal group.

In an interview with Postmedia News Monday, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Shawn Atleo urged Prime Minister Stephen Harper to turn the page on more than a century of Canada's mistreatment of its indigenous peoples.

He called on the federal government to take substantive action in critical areas - by recognizing native treaties and land claims, establishing a public inquiry into missing and murdered aboriginal women, and dropping its "unilateral" and "top-down" approach on how to bolster education for aboriginal children.

The calls came as aboriginals marked the 250th anniversary on Monday of the Royal Proclamation, the document which provided the basis for promises made to First Nations peoples by the British Crown.

Harper's record on aboriginal issues is now under the international microscope, as a United Nations fact-finder began an eight-day trip through Canada to collect information about this country's treatment of its indigenous peoples.

The government's education plan will be the centerpiece of its aboriginal affairs agenda - to be featured in next week's throne speech, and then detailed later this year with the introduction of a First Nation Education Act.

But so far, said Atleo, the Conservative government's approach to working with First Nations on the forthcoming act has been reflective of how federal governments have always acted - "paternalistic at best and assimilationist at worst."

He said that although Harper agreed at a mid-January meeting with aboriginal leaders to bring more "political oversight" to aboriginal issues, his government's consultation on education has "fallen short."

He said aboriginal leaders all agree on the need to improve education for indigenous children, but they are worried the current plan is being unilaterally designed by Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt and that the upcoming act will impose standards that don't reflect indigenous culture, and that funding for aboriginal education won't be increased.

"That would be an example of paternalistic at best," Atleo said.

"Anything less than full supports for language and culture would absolutely fit within a continued assimilationist effort that we still have to this very day," he said.

"I've had residential school survivors who are now leaders in education say to me that the approach (now led by Valcourt) feels like the experience of residential schools.

"This is a pattern that the prime minister has to understand. What would give action to his words of apology in 2008 is to not repeat the pattern of the past and just exacerbate a problem for decades into the future."

In 2008, Harper delivered an apology in the House of Commons to aboriginals for the federal government's involvement in church-run residential schools.

Over many decades, 150,000 aboriginal children were taken from their families and sent to these schools, where attempts were made to assimilate them into European culture, and where many faced physical and sexual abuse.

Valcourt was unavailable for an interview Monday. In July, his department released a "blueprint" that provided hints of what the education act will contain. It indicated the bill will allow schools to be community-operated through First Nations or an agreement with a province, and there will be standards for qualifications of teaching staff and curriculum and graduation requirements for students. There will be regulations governing discipline (such as codes of conduct and policies on suspension and expulsion), hours of instruction, class size and transportation.

The government will share a draft version of the bill with aboriginal leaders before it is tabled in Parliament, but it wants the new system in place by September 2014.

Aboriginal youths are now the fastest growing demographic in the country, and the federal government says it wants to help them "achieve their full potential."

But Atleo said that won't happen without a significant increase in funding.

"I've had senior corporate executives travel with me to northern remote reserves and see first hand kids going to school in trailers at 35 degrees below zero that are not even properly insulated. You walk through that front door and you're walking into the classroom, and the kids are sitting around with their winter boots on and their jackets on."

++++++

First Nation Education Act will be 'transformational', says Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt

BY MARK KENNEDY, POSTMEDIA NEWS OCTOBER 8, 2013

OTTAWA - The Harper government is poised to unveil education reform measures for First Nations children that are so historic it could turn the page on more than a century of economic and social ills faced by aboriginals, says a federal cabinet minister.

In an interview with Postmedia News on Tuesday, Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt trumpeted as "transformational" a First Nation Education Act he will soon introduce in Parliament.

Valcourt also rejected concerns from aboriginal leaders the government might make the mistake of repeating previous "assimilationist" policies from past decades that lay behind residential schools.

The government's education reforms will be featured in next week's throne speech and be a centerpiece of its aboriginal affairs agenda in the coming months.

"We think it is high time, given the importance of population growth of First Nations living on reserves, that these kids get the same opportunities as other Canadians," said Valcourt.

The problem, he said, is that aboriginal children are served by a "non-system" of education - which results in staggeringly high drop-out rates and which puts those young people in an "intolerable" situation.

According to a blueprint released this summer, the upcoming bill will allow schools to be community-operated through First Nations or an agreement with a province, and there will be standards for qualifications of teaching staff and curriculum and graduation requirements for students. There will be regulations governing discipline (such as codes of conduct and policies on suspension and expulsion), hours of instruction, class size and transportation.

"I personally believe that the First Nation Education Act will be transformational, like no other measures that have been taken in 50 years, 100 years," said Valcourt.

He said that as aboriginal parents see more of their young people graduate with a solid education, the effects will ripple throughout communities and help end many of the social problems that have affected First Nations.

"All of these things are affected by what? At the bottom of it all, it's education."

"However you cut it - whether you look at those social indicators. Suicide rates. Violence against aboriginal women and girls. Incarceration rates."

Aboriginal chiefs agree on the fundamental need for improvement in education but they have raised concerns about the "unilateral" and "top-down" approach taken by the Conservative government.

Earlier this week, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Shawn Atleo said the government's approach to working with First Nations on the forthcoming act has been reflective of how federal governments have always acted - "paternalistic at best and assimilationist at worst."

Aboriginal leaders worry the upcoming act will impose standards that don't reflect indigenous culture, and that funding for aboriginal education won't be increased.

But Valcourt insisted he has tried to consult aboriginal leaders and is still hoping to get them onside.

Critics say aboriginal education is significantly under-funded.

But Valcourt boasted the initiative will be "revolutionary" because, for the first time, aboriginal schools will have the stability of predictable funding that has a "statutory base."

Meanwhile, despite continuing calls for a national inquiry into missing and murdered aboriginal women, Valcourt insisted the government won't make that move.

"This issue has been studied extensively," he said.

"I've been in government long enough to know that when a government doesn't want to move or take action, they study or they order an inquiry. So instead of passing the buck, we are taking action."

Earlier in the day, Valcourt met with James Anaya, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples who is conducting a week-long visit of Canada to examine this country's treatment of indigenous peoples.

The Harper government has a record of being publicly disdainful of other UN special rapporteurs and it has already been critical of how Anaya spoke out last year about the living conditions at the Attawapiskat reserve in Northern Ontario.

On Tuesday, Valcourt spoke highly of Anaya, calling him an "honorable" and "intelligent" person who is "very reasonable and practical."

"We are advocates of human rights throughout the world. This is our foreign policy. So we have no objection at all to Mr. Anaya doing his work and seeing for himself how Canada is protecting the human rights of all Canadians, including aboriginals."

NDP Leader Tom Mulcair and some of his party's MPs also met with Anaya on Tuesday.

He said they raised several issues with him, including the government's failure to "respect the rule of law."

"Every step of the way, the federal government spends hundreds of millions of dollars to fight First Nations before the courts," said Mulcair. "And then they don't respect decisions that are invariably in favour of First Nations."

+++++++

From âpihtawikosisân

From Residential Schools to the First Nations Education Act, colonialism continues

Education is widely seen as a key component to future success not only for the individual children who receive that education, but also for the society to which they belong, as a whole. We use graduation rates and post-secondary degree attainment numbers to help determine the efficacy and accessibility of a system of education. More than simply informing us of how many individuals are meeting educational standards, these numbers give us fundamental information about the overall health of a society.

There is no Aboriginal system of education in Canada. This fact is sometimes obscured by misunderstandings of reserve or band schools, or even charter schools that may provide 'indigenous content'. Nonetheless, the system of education that exists in Canada is wholly Canadian, both legislatively and in terms of provision.

Inequality in funding and outcomes for Aboriginal students is a long-standing issue.

Another important fact is that the Canadian system of education is failing indigenous peoples. This is not a matter of debate. Regardless of personal opinions, bigotry and stereotypes, the grim statistics paint a very clear picture. When examining access, graduation rates and post-secondary degree attainment in other countries, we do not blame individuals for egregiously poor outcomes. We do not do this, because education is a social undertaking that transcends individuals and even minority groups. It requires mobilisation of all levels of government, and it impacts every single person living within the boundaries of that system of education.

The stats: outcomes

- A sizable gap in student performance between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students is already present by grade 4, with a widening of the gap by grade 7. (page 4)

- 40% of Aboriginal students aged 20-24 do not have a high school diploma compared to 13% of non-Aboriginal people.

- High school non-completion rates are even more pronounced on reserve (61%) and among Inuit in remote communities (68%). (page 3)

- 9% of the Aboriginal population have a university degree compared to 26% among non-Aboriginal students. 63% of Aboriginal university graduates are women.

The stats: funding

- Non-Aboriginal funding is funded by the provinces. Aboriginal education is funded federally. Non-Status Indians and Métis students receive provincial funding only.

- The federal funding formula for on-reserve schools has been capped at 2% growth per yearsince 1996 despite the need having increased by 6.3% per year, creating at $1.5 billion shortfall between 1996-2008 for instructional services alone.

- Only 57% of federal funding for First Nation students is allocated to First Nation schools. The rest goes to support students attending off-reserve schools. (page 13)

- Unlike their provincial counterparts, First Nations schools receive no funding for library books, librarian's salaries, construction or maintenance costs of school libraries, nor funding for vocational training, information and communication technologies, or sports and recreation. (page 20)

- In 2007, there was a need for 69 new First Nation schools across Canada and an additional 27 needed major renovations. Funding was only provided for 21 new schools and 16 renovation projects. (page 24)

- Despite claims by AANDC to the contrary, a recent federal report confirms that there are severe funding gaps in First Nations education that must be addressed immediately in the short-term, and that long-term improvements must be made with the active participation of First Nations stakeholders.

- Post-secondary funding, available only to Status Indians and Inuit, has been historically inadequate to meet funding needs, and has created a backlog of 10,589 students between 2001-2006 who were denied funding. (page 34)

The First Nations Education Act: The top down approach again

Despite repeated reports (from the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples in 1996, to this latest report tabled in 2012) which recommend that the federal government cease acting unilaterally and without consultation with First Nations, that is precisely what has happened yet again with the First Nations Education Act.

No one has actually seen this Act, which is supposed to be put into place in September of 2014. Instead, a draft plan has been created which will be 'shared with First Nations communities for their input'. The federal government claims it has been adequately consulting First Nations all along, but First Nations leaders have been vociferous in their dissatisfaction with this process. 'Consultation' leading up to the draft was 8 consultation sessions, about 30 teleconferences and some online activities.

The Canadian government has an absolutely dismal record with respect to indigenous education. Why anyone would believe that this time they can get it right, without even truly consulting or working with the people who will be most affected by any policy decision, is a complete mystery.

The first phase, which included eight consultation sessions across Canada, more than 30 video and teleconference sessions, and online consultation activities, - See more at: http://actionplan.gc.ca/en/initiative/first-nation-education-act#sthash.... first phase, which included eight consultation sessions across Canada, more than 30 video and teleconference sessions, and online consultation activities, - See more at: http://actionplan.gc.ca/en/initiative/first-nation-education-act#sthash....

No thanks, we'll do it ourselves

Indigenous education means indigenous planning, development, and control.

Canada needs to finally listen to what indigenous peoples have been demanding for years: that our cultures and languages be given more importance in our systems of education. This focus has been supported by so many publications including (but not limited to):

- Indian Control of Indian Education, 1972

- Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, 1996

- Final Report of the Minister's Working Group on Education, 2002

- United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007

- First Nation Control of First Nation Education, 2010

- Report of the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples, 2011

- Joint FNEC-NAN-FSIN Report, 2011

- Report of the National Panel, 2012

In 1978 and 1979, the Mohawk communities of Kahnawake and Akwesasne opened their own schools respectively named the Kahnawake Survival School (high school) and the Akwesasne Freedom School (elementary, junior high). Focusing on cultural and linguistic immersion and academic excellence, the schools are community funded, the infrastructure was built by the community, and each school has created its own curriculum. In essence, these are private schools which have had to form relationships with provincial authorities to ensure that their students graduate with recognised credentials that will be accepted in post-secondary institutions.

These two school embody the implementation of recommendations in numerous federal reports as well as the stated needs and aspirations of indigenous communities. They are not the only examples of solutions created and implemented by indigenous peoples, but the fact remains that the Canadian system of education does not provide adequate space for the widespread development of an indigenous system of education.

When public funding of Aboriginal education has been so woefully inadequate, and federal control has even been criminally incompetent, it is unacceptable for the Canadian government to yet again attempt to ram through a piece of legislation that cannot possibly fix the problem. You cannot fix the ills caused by a top-down approach by implementing more top-down policies.

Indigenous communities as a whole simply do not have the internal resources to create an entire system of private schooling in order to rectify the horrendous gap that has always existed between native and non-native student outcomes. If you can judge a society by its system of education, then Canada stands clearly guilty of discriminating against indigenous peoples by allowing this situation to continue; and worse, by perpetuating it through another unilateral attempt to 'do what's best for the Indians'.

If you were wondering why so few native people are in support of the proposed First Nations Education Act, I hope you have a better sense of the issue now. My thanks.

+++++++++++

Valcourt urges First Nations education reform 1st, funds later

'The current system is failing these kids,' Canada's aboriginal affairs minister says

By Susana Mas, Oct 09, 2013

Reforming First Nations education is key to closing the learning gap between aboriginal and non-aboriginal students and should come ahead of throwing more federal funding into the system, Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt said. (Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press)

Related Stories

- Aboriginal leader Shawn Atleo warns of 'grave' human rights crisis

- UN special rapporteur, James Anaya, to gauge aboriginal peoples' progress

- Harper government on collision course with First Nations?

Reforming First Nations education is key to closing the learning gap between aboriginal and non-aboriginal students and should come ahead of throwing more federal funding into the system, Aboriginal Affairs Minister Bernard Valcourt says ahead of Parliament's return next week.

While the federal government is poised to introduce a First Nations education act this fall that it would like to see implemented by September 2014, the Assembly of First Nations along with leaders in B.C. have rejected the proposed legislation.

In an interview with CBC News on Tuesday, a week before Parliament resumes, Valcourt cautioned that the federal government won't provide additional funding for First Nations education until reform is passed and a new system is in place.

"One thing I can guarantee: Some people they call for funding, funding, funding. Well, funding will not replace reform."

"Reform will take place, funding will follow. But funding will not replace reform because the current system is failing these kids," Valcourt said.

On Monday, Shawn Atleo, the national chief for the Assembly of First Nations, outlined three conditions the federal government must meet to achieve reform - notably "fair" and "sustainable" funding.

"This means ending arbitrary caps and delays that characterize the current failures of the system," Atleo told reporters during a news conference in Ottawa.

However, when asked by CBC News whether the proposed legislation currently meets the conditions as outlined by Atleo, the minister of aboriginal affairs said "absolutely."

"All of the points that he [Atleo] made are covered, and that's the intent of what we want to propose by way of legislation," Valcourt said.

Atleo also said a First Nations education act must put First Nations "in the driver seat, designing the delivery and implementation of education."

Education reform must also include "support and respect for our languages and our cultures," the national chief said.

Education reform expected in throne speech

First Nations education reform is expected to be featured in Tuesday's throne speech, and will also be the centrepiece of this government's aboriginal policy.

Valcourt said aboriginal policy will focus on education, skills development and improving the lives of aboriginal families living on reserves.

The minister explained that his department published a "blueprint" for First Nations education in July at the request of First Nations leaders and stakeholders.

Publishing a draft of the legislation this summer was not only a way for the federal government to show that it was being "transparent" with First Nations, but "more importantly," Valcourt said it was to show "that we were listening."

The "blueprint" follows on the work of the 2012 national Panel on First Nation Elementary and Secondary Education, and following months of consultation.

"The aim of this is to ensure that we have a system which we don't have right now," the minister said.

Valcourt said he spoke with James Anaya, the UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples, on Monday about First Nations education and other topics.

Young aboriginals are the fastest-growing demographic group in the country, making it crucial to give them the same opportunities for education as non-aboriginal students, the minister said.

"It is imperative that in terms of skills development and jobs training, that we do all we can to ensure that this fountain of human resources on reserves can benefit all of Canada by their good work," Atleo said.

Despite the current opposition to the proposed education reform, Valcourt said the federal government is making progress with "willing First Nations."

Anaya is now on his third day of a nine-day visit to gauge the progress Canada has made since 2004, when his predecessor made the last trip here.